Sorry, Hayao

WWII gets filtered through another child’s eyes in Shinnosuke Yakuwa’s adaptation of Tetsuko Kuroyanagi’s 40-year bestseller.

Totto-Chan: The LIttle Girl at the Window

Director: Shinnosuke Yakuwa • Writers: Yosuke Suzuki, Shinnosuke Yakuwa, based on the novel by Tetsuko Kuroyanagi

Starring [Japanese]: Liliana Ono, Koji Yakusho, Shun Oguri, Anne Watanabe, Karen Takizawa

Japan • 1hr 54mins

Opens Hong Kong March 21 • I

Grade: B

Sorry, Hayao Miyazaki stans, but Shinnosuke Yakuwa’s Totto-Chan: The Little Girl at the Window | 窓ぎわのトットちゃん is, for all intents and purposes, the same story as Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron told better. I don’t care if it won an Oscar (it’s a Paul Newman win anyway) and I don’t care if Miyazaki is “the master”. Admittedly Totto-Chan can’t hold a candle to Miyazaki’s artwork; it’s lovely in a low-key Laid-Back Camp kind of way, but it’s not as blissfully demanding as anything from Ghibli. Still, the story about a school for special learning needs kids facing down the Second World War and the rise of right-wing Imperial Japanese fervour (no we’re not talking about [Country Name Here] and when is this shit going to stop?) has a stinging anti-nationalist message buried within its sweetness and light and children finding support and companionship with each other.

Based on the 1981 memoir by the incredibly popular and enduring Tetsuko Kuroyanagi – now 90 – Totto-Chan isn’t quite as dark as the recent Kitaro prequel (I’m still traumatised), but it doesn’t shy away from the realities even the youngest and least equipped among us must sometimes reconcile with. Totto-Chan is about the little girl, but it’s also about the way the rest of us drop the ball when it comes to neurodiverse kids, and a love letter to the schools that offer alternatives.

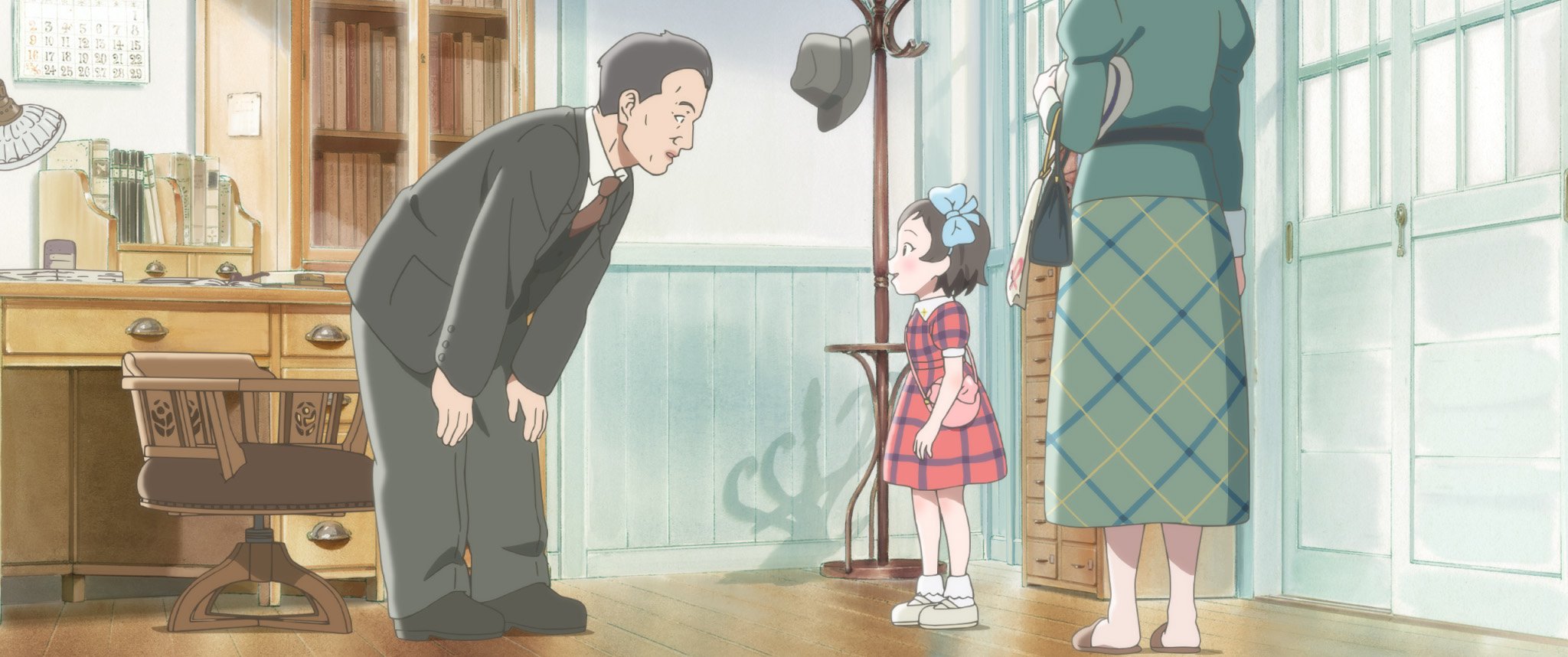

Totto-Chan (Liliana Ono) is a rambunctious, easily distracted seven-year-old that gets thrown out of the public school she attends in Tokyo. She attracts a group of travelling musicians to the window of the school, to the delight of her classmates and consternation of her frazzled teacher (this is actually a pretty funny scene). Anyway, she gets expelled for being disruptive, prompting her concert violinist dad Moritsuna Kuroyanagi (Shun Oguri) and mom Cho (Ken’s daughter Anne Watanabe) to enrol her in Tomoe Gakuen, a school specialising in alternative teaching, embracing art and encouraging freedom of expression. Cho takes her to meet the school’s progressive, innovating principal Sosaku Kobayashi (the sonorous Koji Yakusho), he welcomes her, and needless to say Totto-Chan blossoms.

Part of her blossoming process is a direct result of her friendship with Yasuake, a quiet, reserved boy with polio, because this is the 1930s and there’s no polio vaccine yet. He’s got a weak leg, a weak arm, and can’t mess around with the other kids. He hangs out in the school’s train car classroom reading a lot, but Totto-Chan’s not having it. She drags him out of his self-imposed isolation by sheer force of will. And though she brings him out of his shell, he compels her to learn empathy. There’s a peaceful bubble around Tomoe Gakuen, a safe place where all the kids accept each other – no questions asked – and gain something for it. So it’s gutting that the context of the story is Japan’s increasing hardcore militarisation and eventual entry into WWII, all the while demanding new behaviour from “good” citizens. The school closes.

Doraemon director Yakuwa makes an assured leap into adult filmmaking with Totto-Chan, and lets loose with some gorgeous visual storytelling. The little details that propel the narrative momentum are elegant and graceful; they demand you pay attention but never slip into Easter egg territory. The backgrounds change slowly with the inexorable march to war: there are more soldiers on the streets, more Imperial flags, fewer sweets in the vending machines, the regular JR ticket man suddenly disappears. And yes, the use of interstitials drawn with entirely different animation styles to depict Totto-Chan and Yasuake’s internal growth is an old trick. But their fantastical inner dialogues are some of the film’s most creative sequences. Ironically, Totto-Chan isn’t drawn as the most physically appealing character ever put to anime: her forehead is giant and she looks like she’s always wearing a busted wig, but that gives the kids at school, and viewers, a chance to focus on her innate sensitivity and generosity. Her admission interview with Mr Kobayashi takes a melancholy turn when she asks him why everyone thinks she’s a troublemaker and it makes you pull for Totto-Chan. As a film, Totto-Chan: The Little Girl at the Window takes a number of thematic cues from Miyazaki, not surprising considering he and Kuroyanagi are peers(ish). But Yakuwa’s spin on this story in some ways is more focused and more ambitious, and deserves a look. The master would probably be thrilled. — DEK