The Long Good-bye

Here’s hoping Miyazaki decides on one more kick at the can, because he really deserves to go out on a higher note.

The Boy and the Heron

Director: Hayao Miyazaki • Writer: Hayao Miyazaki

Starring [Japanese]: Soma Santoki, Masaki Suda, Aimyon, Yoshino Kimura, Takuya Kimura, Ko Shibasaki, Jun Kunimura

Japan • 2hrs 4mins

Opens Hong Kong December 15 • IIA

Grade: B

I know I’m going to get some slings and arrows for this, but whatever.

At 82 years old, after steering the incredibly influential Studio Ghibli since its launch in 1985, inspiring everyone from Pixar’s foundational animators to Travis Knight (Kubo and the Two Strings) and other Japanese giants like Makoto Shinkai (Suzume), and cranking out stone classics Princess Mononoke and Howl’s Moving Castle (better than the admittedly tremendous Spirited Away, fight me), Hayao Miyazaki has earned his retirement. You know, the one he announced in 2013 after completing The Wind Rises. After all that producing, and 12 features of his own, he’s earned a stinker too. Steven Spielberg has The BFG. John Woo has Manhunt. It’s allowed. Un-retiring and coming back with one more, The Boy and the Heron | 君たちはどう生きるか, makes him The Who or the Michael Jordan of animation, particularly when the “comeback” product is more of a greatest hits than anything new and compelling. Based on artwork alone, no Miyazaki film will ever be skippable; there’s going to be something to boggle at on the screen. Ditto for sentimentality. Miyazaki knows where our heartstrings are, when to tug on them, and how hard. His average is better than most filmmakers’ best. But this time around it’s all just a bit too familiar to be outstanding Miyazaki.

How familiar? It’s 1943 Tokyo and young Mahito Maki (voiced by Soma Santoki) loses his mother one night in a terrible hospital fire – probably the film’s strongest single sequence – after which his father, Shoichi Maki (Takuya Kimura), relocates them to the countryside (Miyazaki’s own, well documented life). His father works in munitions (Rises again) making parts for bomber planes, a profession the sensitive Mahito tries his damnedest to makes sense of. Also living on this estate is his mother’s sister Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura), who’s not just auntie but his new mother too. She warns him about an ornery Grey Heron (Masaki Suda) that’s been hanging around, and who lures Mahito towards a derelict tower by claiming his dead mother is on the other side of its gate. When Natsuko wanders in, Mahito goes after her, ostensibly on a rescue mission but really to explore a highly metaphorical space where he can grow up and wrestle with his (and our) relationships with nature (Nausicaä), violence (The Wind Rises), and grief.

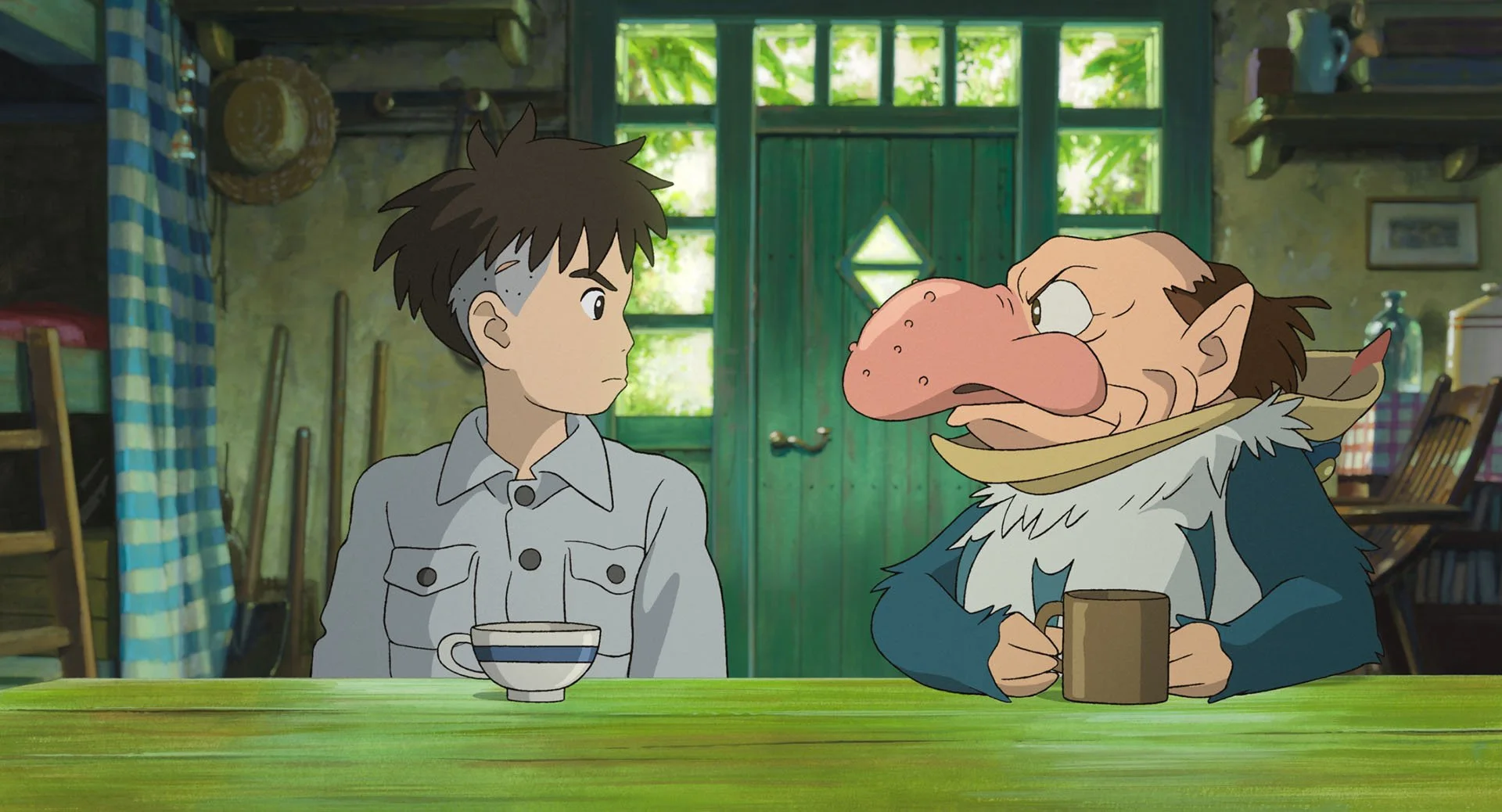

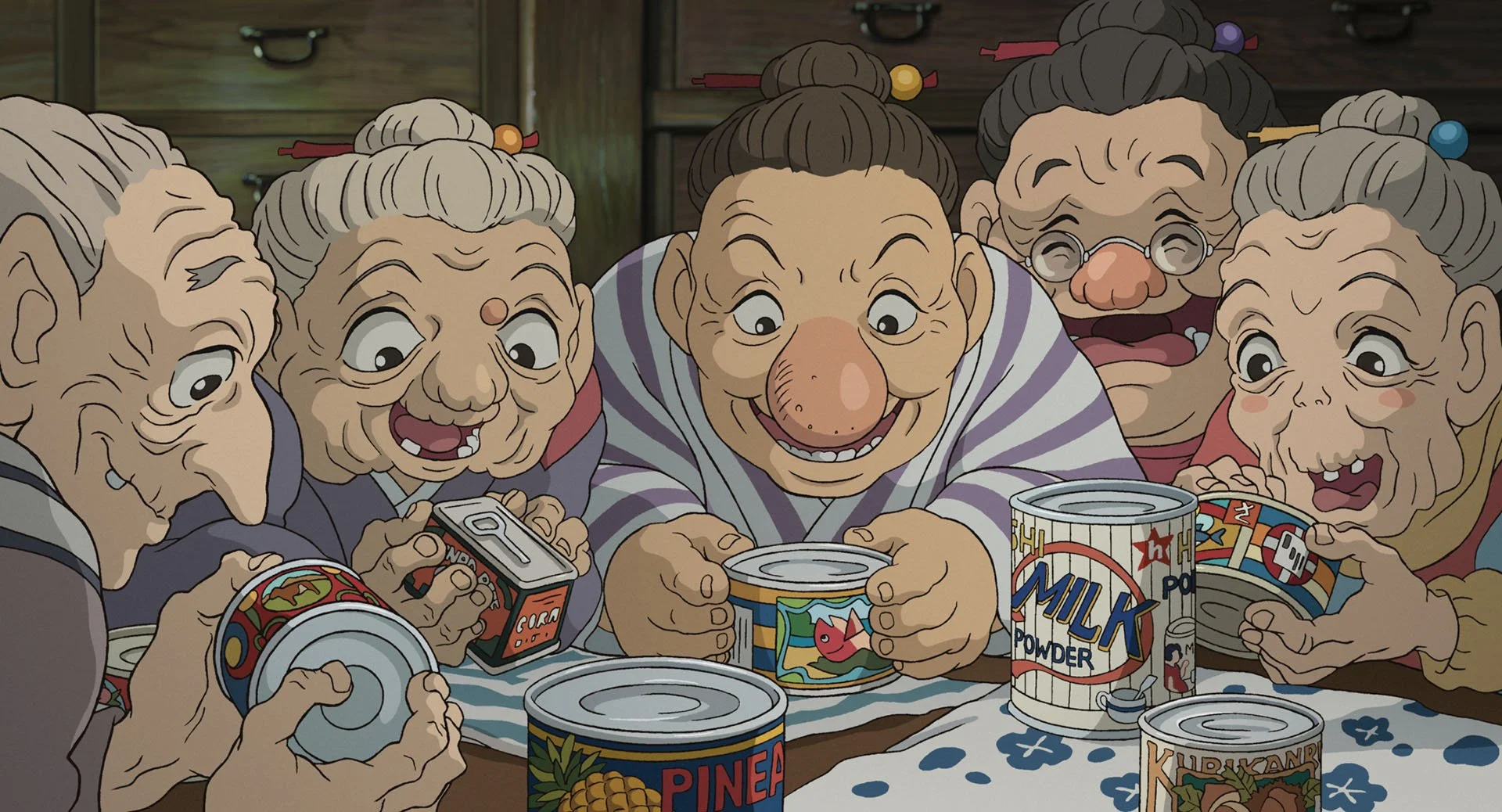

The fantastical alternate universe is lorded over by Natsuko’s Granduncle (Shohei Hino, or Mark Hamill in the English dub, which yeah, cool), and it’s a fracturing place, and fortunately Mahito, Grey Heron – who’s actually a warty little man in a suit – and chain-smoking housemaid Kiriko (Ko Shibasaki) find a guide in the Mononoke-ish sailor they meet, Himi (pop star Aimyon). Seems the warmongering Parakeet King (Jun Kunimura) and his army are looking to usurp Granduncle and raid his stronghold, a magical castle (Howl’s) where Natsuko is about to give birth. During the journey they meet the adorable Warawara creatures (very My Neighbor Totoro-esque), eventually defeat the Parakeets and bring them back into the fold in the real world. There’s more, but that’s the gist.

Wading through the slightly muddled yet somehow bloated story takes work; Miyazaki’s best has never been a chore. The meta layer provided by a book Mahito reads, left by his mother, doesn’t enrich the story. It just confuse it. Can you image being fluent in Japanese and thinking this might be an adaptation of Genzaburo Yoshino’s 1937 coming-of-age novel, How Do You Live?, in light of Heron’s essential subject matter and its Japanese title translating to… How Do You Live? That’s not as thoughtful as it thinks it is. As Mahito grows up, comes to accept Natsuko as part of his life, and reconciles both his grief and his father’s place in the kind of war machine he confronts with the parakeets, the themes emerge, the story threads come together, and a couple of the characters distinguish themselves; Kiriko is particularly vivid. Sadly, one of them is not Mahito, who remains a cypher for most of the film, rendering great swathes of it simply frustrating. You will glance at your clock a few times – then it stops. Not ends. Stops. Sorry, but The Boy and the Heron is far from Miyazaki’s best, and it makes for a middling swan song. More like a seagull: strong enough and able to soar, but not quite as graceful. — DEK