Here, Kitty

Think of the Ghost Cat as Studio Ghibli lite, with a touch more attitude.

Ghost Cat Anzu

Directors: Yoko Kuno, Nobuhiro Yamashita • Writer: Shinji Imaoka, based on the manga by Takashi Imashiro

Starring [Japanese]: Mirai Moriyama, Noa Goto, Munetaka Aoki, Shingo Mizusawa

Japan / France • 1hr 34mins

Opens Hong Kong Nov 28 • I

Grade: B+

There’s something effortful about Ghost Cat Anzu | 化け猫あんずちゃん that’s at once its biggest failing but also it greatest strength. Anyone who doesn’t see the fantastical Studio Ghibli of it all is either not paying attention or has issues with Hayao Miyazaki. Fair. His and Ghibli’s brand of aggressive whimsy can be a bit much at times, a whimsy that’s almost always attached to an earnestness that can be stomach-churning. Ghost Cat Anzu has a great deal of the whimsy and much less of the earnestness. Oh, it’s got that too, but at manageable levels that are also muted by some welcome low-key snark and a brilliant, layered voice performance by Mirai Moriyama (Shin Kamen Rider) as the ghost cat of the title.

Ghost Cat Anzu got a world premiere at Cannes this past May, a not inconsiderable feat, but also one that comes cursed with sky-high expectations and/or a singular type of derision saved for Cannes and Sundance “hits”. But Anzu defies the odds and reveals itself as a slightly oddball charmer; a standard coming-of-age story about a child dealing with death (seriously, Japan, what’s with all the dead parents in anime?) and growing up just enough to find both closure from grief and the value in the living world around them. Aside from some pitch-perfect voice acting, Anzu’s luscious rotoscope animation and live audio dub set it apart from its peers, and in a backhanded kind of way makes it that much more affecting.

As he’s being chased by angry Yakuza, compulsive gambler Tetsuya (Munetaka Aoki, Godzilla Minus One, The Roundup: No Way Out) flees Tokyo with his 12-year-old Karin (Noa Goto) for the tranquil community of Iketeru where his father lives. Osho (Keiichi Suzuki) is the resident monk of Sousei-Ji, and after it becomes clear why Tetsuya has dropped in for a visit, he reminds his no-goodnik son he has no money for him to borrow. Tetsuya does the only thing he can: he dumps Karin there and heads back to the city to deal with his debts.

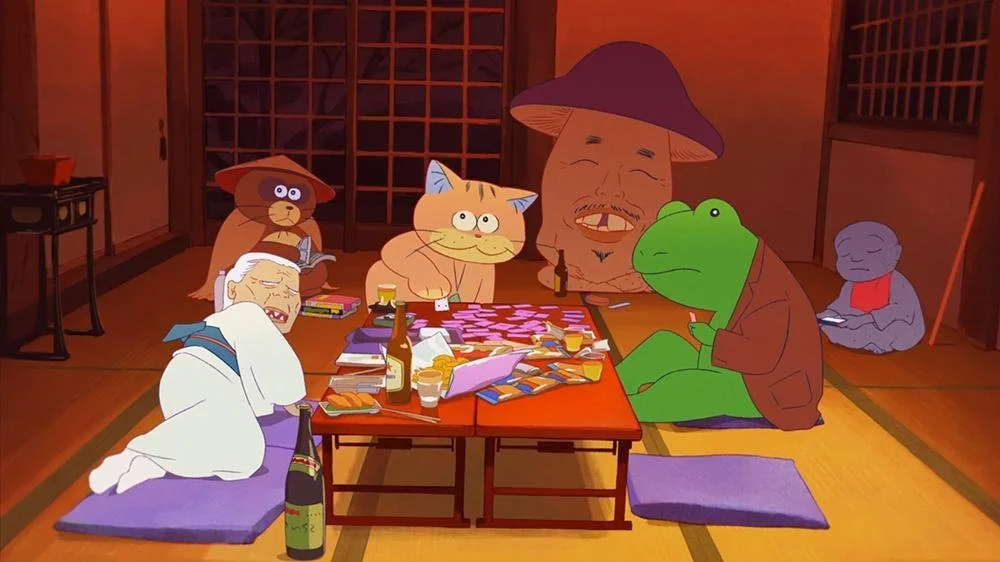

Karin, naturally, does not want to be in this backwater town and is pissed she’s not spending summer at cram school with her crush. She waits impatiently for her dad to come back and quietly mourns the recent death of her mother Yuzuki (Miwako Ichikawa). Now, also living in the temple is Anzu, a 37-year-old (!) former stray cat Osho adopted, who rides a bike, walks and talks like a human, and has an unhealthy taste for pachinko. No one in town finds his presence strange – Anzu has a booming massage side hustle? – and in turn he looks out for everyone; he plays a game of, uh, cat and mouse with the God of Poverty (Shingo Mizusawa) and gets him off a local’s back. He also has a crew of other spirit realm folks he hangs out and plays cards with, a crew that ultimately takes Karin under its wing. The ghost party plays a crucial role in rescuing Karin and Anzu from the underworld and its king, Enma, when Karin goes looking for her dead mother.

Directors Yoko Kuno and Nobuhiro Yamashita combine their skills as an animator and storyboard artist and live action television and film director, respectively, to genius effect here, and their choice to rotoscope over actors and record dialogue live gives the film an intangible texture that works to its advantage – even if you don’t realise it. There’s a fuzzy, appealing vibe to Ghost Cat Anzu that sucks you into the story despite Shinji Imaoka’s script spinning its wheels for at least two acts. That would be a much bigger issue if the characters weren’t so real – Karin is often hard to like and I don’t care if she’s sad; a couple of boys in town are hilariously off the mark rebels – and the world Kuno and Yamashita create weren’t so rich. Imaoka eventually weaves the various threads together, so it makes the picaresque of the first two acts worth the effort, particularly when a giant, otherworldly cat riding a scooter is entirely normal, the gateway to Hell is located in a Tokyo office building toilet bowl, and Hell itself is imagined as a Mad Men-era office complex. It’s brilliant and the film’s stand-out set piece, and it deserves its own movie. And you know what? Yeah, I’ll say it: This was a whole lot more creative than The Boy and the Heron. Sorry (not sorry).