Shopping Bad

Kiyoshi Kurosawa dives into the hellscape of online retailing and comes up with half a good movie.

Cloud

Director: Kiyoshi Kurosawa • Writer: Kiyoshi Kurosawa

Starring: Masaki Suda, Daiken Okudaira, Kotone Furukawa, Masataka Kubota, Yoshiyoshi Arakawa

Japan • 2hrs 8mins

Opens Hong Kong Jan 9 • IIB

Grade: B-

Early on in Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s latest foray into contemporary Japan in Cloud | クラウド, we get the sense something is ever so slightly amiss. That uneasy feeling can probably be chalked up to the 1.66:1 aspect ratio Kurosawa’s gone for, essentially the shape of 16mm and European arthouse films – still occasionally deployed for its ability to telegraph the claustrophobic and discombobulating. Blue Valentine, A Clockwork Orange and The Witch are all 1.66. It’s not quite Academy ratio or 4:3, which olds will remember as standard television shape, and it’s certainly not the familiar widescreen that’s the norm now (or the 2:1 Netflix has made nearly ubiquitous). Now when it is used, it’s just unfamiliar enough on an intuitive level to put us all on the back foot, which is where Kurosawa wants us for Cloud.

After online reseller Ryosuke Yoshii (Masaki Suda, Father of the Milky Way Railroad, We Made a Beautiful Bouquet) buys an entire pallet of “therapy machines” from its inventor Tonoyama (Masaaki Akahori) for JPY30,000 a piece, he takes them home, takes a few sexy photos of the product and drops them on his website for JPY200,000. He turns a tidy profit, which Ryosuke’s girlfriend Akiko (Kotone Furukawa) entirely approves of. Sometimes he buys knock-off handbags, sometimes limited edition action figures, but every time he buys low and sells high, often unethically. But he wants to be more independent, so he dumps his quasi-partner Muraoka (Masataka Kubota) – the guy who turned him onto the scheme – leaves Tokyo for an idyllic house by a lake in the mountains and starts over with a new assistant, Sano (Daiken Okudaira). But a dead rat on his doorstep, giant machine parts through the bedroom window and a string of vitriolic messages in a chat group suggest things are not going to go Ryosuke’s way.

Kurosawa’s breakout films, Cure and Pulse in the late 1990s, branded him a horror filmmaker because people are dumb that way, despite him also delivering dramas like Bright Future and Wife of a Spy. If there’s one thing Kurosawa’s proved it’s that he’s a master at capturing the stresses of modern urban life and the unknowability of people, and he’s revelled in dropping average (usually) dudes into fucked up situations to watch them squirm when they reach their personal tipping points. For Cloud you can add the super-current subjects of internet mobs and their seemingly infinite capacity to stoke groupthink and/or create comfy echo chambers, how those allow mild irritation to blossom into deadly rage, the security of technological anonymity and the insecurity of modern economics. Really, who the hell is Sano? Is peddling grey market-adjacent junk really going to satisfy Ryosuke? And how much responsibility is anyone supposed to take for buying a purse, sight unseen, from shady retailers? Can I really dox a bitch and trash his house if I’m unhappy – and be cheered on for it? Evidently the answer is “Yes” if the to response Brian Thompson’s murder is to be believed. Now, wrap it all up in tight and tightly controlled compositions that slowly build out a mystery and a sense of dread via visuals and you’ve got a premium Kurosawa joint.

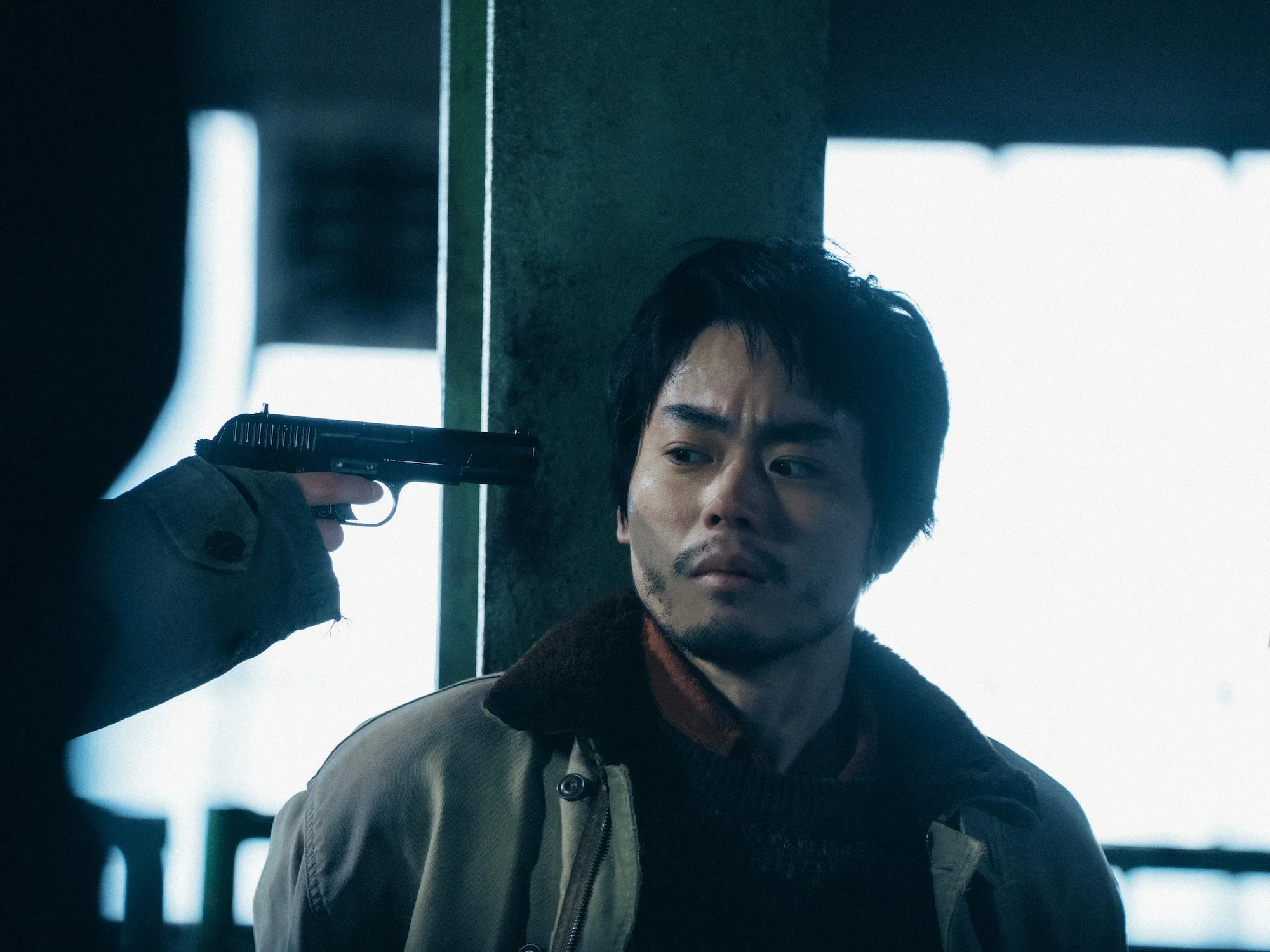

Until you don’t. For all its au courant debate and thought-provoking ideas, Cloud almost floats away in its second hour when Ryosuke’s chickens come home to roost. Feeling aggrieved for various reasons, Tonoyama and Muraoka team up with Ryosuke’s old boss Takimoto (Yoshiyoshi Arakawa) and a random pissed off guy to exact revenge on him for… reasons. The quiet contemplation of the first hour is abruptly dumped in favour of a Free Fire-esque (Ben Wheatley’s movie, not the game) shoot-out, the siege of The Equalizer, or any other rote action thriller that comes to mind. Ater so much quiet apprehension the conventional resolution is a let-down. Suda is fine in playing Ryosuke’s thoughts and feelings close to the chest, but the gratuitous final act retcons him into seeming blank, not cagey, cautious or underhandedly ambitious – which he did before. Tonoyama, Muraoka and Takimoto’s motivations are razor thin, unearned and clang with all that came before they hatch their plot; Furukawa may as well have not been there for all Akiko contributes to the story – unless feckless, materialistic girl who can’t work a goddamned coffee maker says something profound that hasn’t occurred to me yet.