The Music Man

Calling all film nerds. a comprehensive, and sometimes exhausting, breakdown of film music is here in the shape of the must-see/hear ‘Ennio’.

Ennio

Director: Giuseppe Tornatore • Writer: Giuseppe Tornatore

Featuring: Ennio Morricone, Hans Zimmer, Quentin Tarantino, John Williams, Bernardo Bertolucci, Oliver Stone, Quincy Jones, James Hetfield

Italy / Belgium / Netherlands / Japan • 2hrs 36mins

Opens Hong Kong June 1 • IIB

Grade: B

His film scores are so synonymous with great film moments now that it’s kind of hard to imagine Italian composer Ennio Morricone as a pop star, but he was. He composed and arranged a bunch of Italian pop hits in the 1960s, making him a proto-Danny Elfman (who was in Oingo Boingo before becoming Tim Burton’s go-to scorer) or Trent Reznor (the Nine Inch Nails frontman won an Oscar for Soul) or Jonny Greenwood (Radiohead guitarist and Paul Thomas Anderson’s guy). And you know what? His stuff from the ’60s really swings, baby. I might honestly like some of those better than “Closer”, and Giuseppe Tornatore’s comprehensive documentary about Morricone, Ennio, probably does too.

For most of us Morricone, who has a whopping 530 IMDb credits for the record – 530, only James Hong comes close (457 as of right now) – is still best known for his groundbreaking (and it was) and iconic (it still is) screeching whistle from 1966’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, Sergio Leone’s defining spaghetti western. Morricone fought writing it because, evidently, film composing was trashy and lowbrow at the time. But here we are, over a half-century later still riffing on it. It’s one of the most recognisable pieces of music ever put to film.

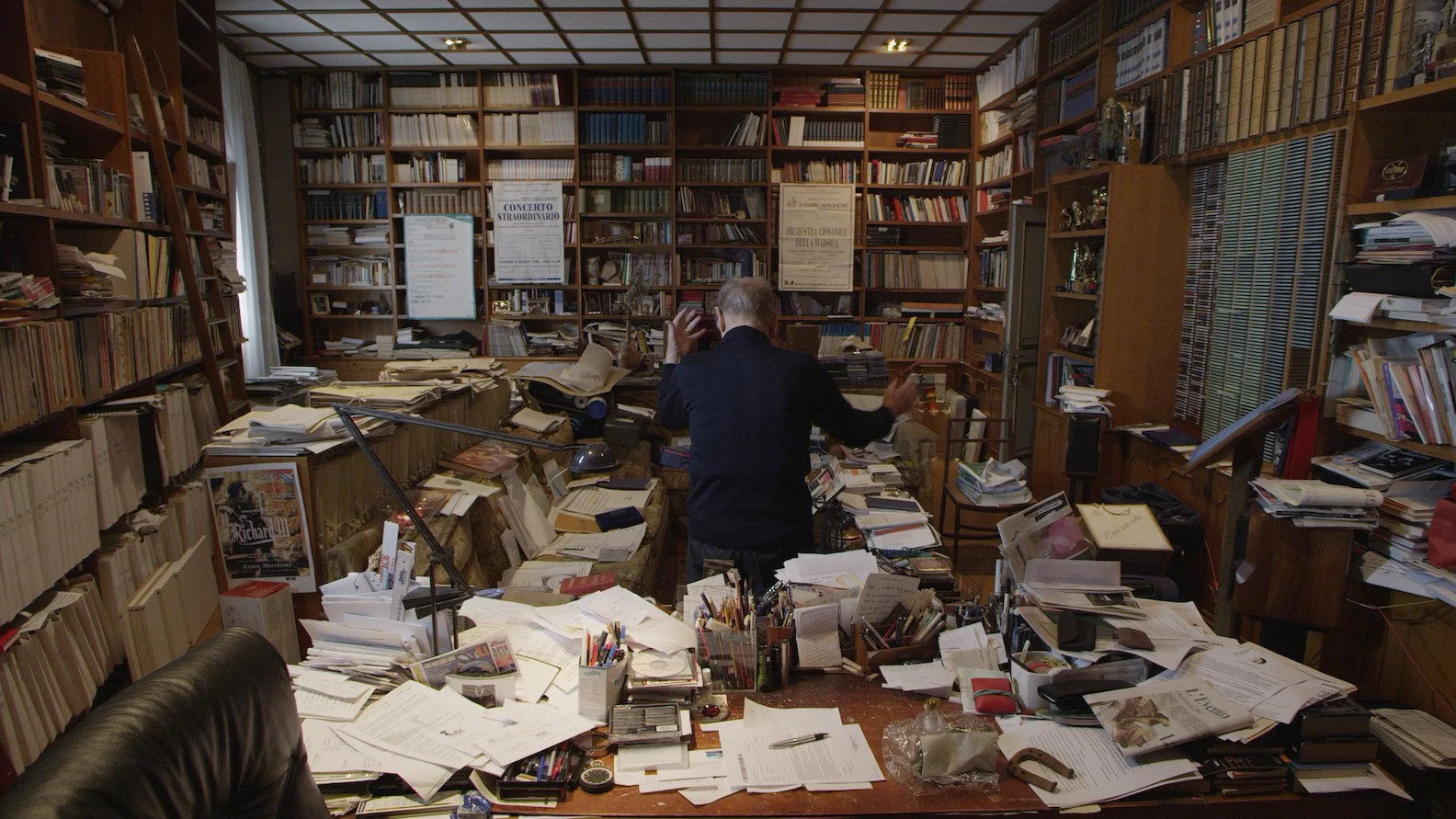

Ennio is a film by a film nerd, for film nerds. It’s exhaustively researched, chronologically fastidious, technically enlightening (if you don’t know what a motet is you will by the end), and it’s a bonus Italian Cinema 101 seminar. But at the end of the day it’s also a little cold. Scores of heavy hitting music and cinema types talk about what made Morricone – who died in 2020 at the ripe old age of 91 in his beloved Rome – a genius, an innovator and a legend. Among them are Italian musicians Zucchero Fornaciari, Ornella Vanoni, Laura Pausini, and Caterina Caselli, foreigners like Quincy Jones, Bruce Springsteen (!), Pat Metheny, and Metallica’s James Hetfield (!!), other film composers like Hans Zimmer and John Williams, and of course directors who count Morricone as a storytelling partner: Quentin Tarantino, Oliver Stone, Barry Levinson, Dario Argento, Bernardo Bertolucci, Barry Levinson, Lina Wertmüller, Marco Bellocchio, Paolo and Vittorio Taviani, and Clint Eastwood. Morricone’s scores may not spring to mind as quickly as Williams (Star Wars, Jurassic Park), Zimmer (Inception) or Vangelis (Chariots of Fire) do, but Roland Joffé’s The Mission isn’t quite the spectacle without that choral, pan flute-y background. Ditto for Gillo Pontecorvo’s neo-realist classic The Battle of Algiers, and Tornatore’s own Oscar winner, Cinema Paradiso. The list goes on. Each interview contextualises Morricone’s work, and makes a case for him being one of, if not the GOAT film composers.

What Ennio doesn’t do is give us much insight about what made Morricone Morricone. A big chunk of the film, roughly the first hour, is dedicated to his childhood under the watchful eye of his father, a trumpet player, who treated the instrument as part of a job that payed the bills (Italians, amirite? The Sistine Chapel was just another paying gig for Michelangelo). Also factoring into Morricone’s musical life was the composer and teacher Goffredo Petrassi, who’s constant dismissal of film music supposedly stuck with Morricone for most of his life. Also with him most of his life was Maria, his wife of over 60 (!!!) years. Ennio flatly states she played a major part in his work. And though Morricone himself refers to all these people on multiple occasions, neither he nor any of the scads of interviewees really spill the tea on how they influenced his work. Were the pleading strings of Once Upon a Time in America the work of a man at the peak his creativity still pleading for approval? Is Burn! the wilfully eclectic work of an artist finally comfortable flexing his muscles? Is the elegant bombast of The Hateful Eight a final “Nyah!” to his detractors? Who knows? No one’s really saying, because Morricone doesn’t broach the subject and Tornatore doesn’t ask.

Of course, if you’re seeing Ennio in a real cinema, on a big (or biggish) screen, accompanied by state-of-the-art surround sound it doesn’t matter one bit where his inspiration came from, or who shamed him into some of the greatest scores ever. Because just listen. To. That. Music. Bravo. — DEK

Morricone’s Greatest Hits

The Untouchables (1987), d: Brian De Palma

Those opening credits! De Palma’s awesome thriller about Al Capone is worth it for Robert De Niro’s rant about destroying FBI man Eliot Ness – and his dog.

Salò (1975), d: Pier Paolo Pasolini

For film students only. The confrontational Pasolini’s reviled, adored, genius, dumb, oft-banned anti-fascist art horror epic was his last before his murder.

U Turn (1997), d: Oliver Stone

Stone’s absurdist, neo-noir stars Sean Penn and J.Lo in hyper-saturated dusty, sleazy noir antics. Sweaty fun if you’ve already seen Red Rock West.